Part 90: The Rhine Crisis

Chapter 10 - The Rhine Crisis - 1870 to 1876It had been a long time coming, but in the early morning dew of the 1st of January, 1870, the South German Union and Dual Monarchy finally came to blows over the Rhine.

Even before the first bullets were fired, the Dual Monarchy was very confident in their chances - they had fought Europe to a standstill once before, and they could certainly do it again. In fact, the French prime minister immediately stated his intentions to secure the Rhine and dismantle the impressive Palatinate fortresses, along with several other war objectives, including the cessation of Andalusi Granada to the Almoravid Sultanate.

And the Berbers were all too eager for war, having spent the past decade earnestly modernising their army and navy, determined to improve on their disastrous performance in the Iberian War. The Almoravid Fleet was dispatched to the Straits of Gibraltar, with the Moroccan leadership determined to secure the vital passageway as quickly as possible.

The Andalusi weren’t capable of challenging the Berbers on the seas, especially as rumours began to spread regarding their revolutionary new flagship, said to be steam-propelled, torpedo-fitted and clad entirely in iron and steel. The Andalusi Navy was still comprised of wooden ships, so the high command immediately abandoned any notions of challenging for the Straits. That question would have to be settled in another war.

That didn’t mean they were helpless, this war would be decided in Europe. The Andalusi Army in 1870 numbered almost 90,000 soldiers organised into three smaller forces, with their supreme commander being Astifadat al-Qutili, a veteran general who’d served with distinction in the Iberian War.

With orders quickly relayed from Qadis, Astifadat took two-thirds of the Andalusi Army and marched northwards, proceeding cautiously into Occitania with almost 60,000 well-drilled, highly-experienced soldiers - the very cream of the crop.

The final third would remain in Iberia under the command of Zafir ibn Yusuf, with stern orders to repel the inevitable Moroccan invasions.

And like clockwork, the Berbers crossed the straits just a few days into 1870, with over 30,000 soldiers seizing the beachheads of Qadis and Jabal Tariq in bloody assaults.

Zafir immediately pushed southward, clashing with them a few miles east of the capital. Fierce fighting followed, and victory was proclaimed on the 2nd of February, with newspapers in Qadis quickly jumping on the euphoric bandwagon, boldly predicting that Andalusi soldiers would be in Marrakesh before year’s end.

To the east, meanwhile, King Apanoub of Egypt was eager to exploit the outbreak of war in Europe. With the Moroccans distracted by the Andalusi, he finally felt confident enough to declare on Cyrenaica, an emirate firmly within the Moroccan sphere of influence.

And further north, the Russian Empire declared war on Scandinavia-Novgorod, similarly looking to take advantage of the chaos in the west.

In Central Europe, the South German Union found itself fighting two different wars on two different fronts, as the Hanoverians quickly descended on Nuremberg from the north whilst the French clashed with the Bavarians in a string of battles along the western front.

It quickly became evident that the South Germans weren’t prepared for a two-front war, however. So in a calculated move, the Archduke of Bavaria decided to concede defeat to Hannover, ceding Nuremberg in return for peace - a shameful and temporary peace, but one that they desperately needed.

And now that they could channel their full strength to the west, the Dual Monarchy was forced to reply in kind, redeploying tens of thousands of soldiers to the German front. This left Occitania sparsely-defended, allowing Andalusi armies to quickly sweep northwards, meeting little resistance until they reached Cahors.

Just north of the city, a French-English army was waiting to meet them, with their numbers quickly climbing to eventually count 45,000. Marshal Astifadat wasted no time in engaging them, utilising the wide, flat grasslands to deploy his full strength to the battlefield, hoping to overwhelm French positions and force them to retreat eastward.

The ensuing battle would not be so simple, however, with French infantry repelling these early assaults with heavy casualties. The fighting quickly deteriorated into close-quarter sparring after that, only shifting in favour of the Andalusi when two hussar brigades thundered into a desperate charge to foil fate. It was this attack that finally broke the French line, and as panic rapidly spread through enemy ranks, the Andalusi launched another counter-attack and shattered French formations.

Despite suffering the lion’s share of casualties, spirits soared with the hard-won victory, spurring the Andalusi to immediately push northwards and seize another important (and more decisive) victory.

This string of victories would be tempered within weeks, however, with French armies securing control over the Rhine. This was followed by a sustained offensive deep into Bavaria, with München briefly sighted before the Germans were able to counter-attack, aggressively chasing the French back across the border.

This summer campaign alone had cost hundreds of thousands of lives, and neither side had anything much to show for it. More bad news would descend on Paris that very same month, with Irish armies swarming across the border and seizing Manchester, as had become tradition.

The Dual Monarchy was now at war on three different fronts, facing three wronged enemies - this, it would seem, was the steep price of continental domination.

Despite facing unassailable odds, however, this war was far from over. The Almoravid Fleet landed an army at Lishbuna late in the winter of 1870, with the 20,000-strong force quickly seizing the city and pushing eastward. They didn’t get very far before being confronted, fortunately, with the Andalusi bringing their advance to a sudden halt at al-Adna.

The victory was Andalusia’s, but whilst this battle had been raging, another Berber army had disembarked near Jabal Tariq, quickly marching on Qadis from the coastal fortress. Zafir ibn Yusuf rushed southward by railway and reached Qadis in the knick of time, battering into the Berbers just as the city’s walls were breached.

The siege of Qadis ultimately proved to be a ruse, however, flawlessly pinning the entirety of Andalusi forces in Iberia down in one place. Another 15,000 Berbers immediately reinforced the fighting, pouring onto the battlefield from concealed locations further east, quickly surrounding large parts of the Andalusi army in a stunning envelopment manoeuvre.

From there, the battle could only end in one way.

Almost the entirety of the army was killed or captured in a disastrous massacre, with the few survivors retreating into Qadis, where the garrison had already begun digging trenches around the city boundaries.

Trenches would not be enough to repel the Berbers, however, with artillery and cannonry quickly hauled into position from the coast. Qadis would be under heavy bombardment before day’s end, with the city mercilessly shelled whilst being blockaded at sea, all of which came together to bring about a quick and decisive end to the siege. By March of 1871, Qadis had fallen to the Berbers.

And the next few weeks would not be pleasant for its inhabitants, as the Berbers plundered and pillaged with impunity, killed and raped indiscriminately, reft and ravaged mindlessly. Monuments and artefacts were hauled from the city and across the straits, quickly transported to the isolated Almoravid stronghold of Marrakesh, where they were flaunted and paraded down the crowded streets of the city.

Forty years later, Morocco had finally avenged the Sack of Marrakesh.

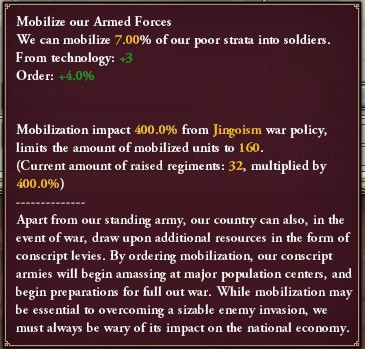

Ordinarily, this would’ve spelled the end of the war, but the Andalusi were made from sterner stuff. Sultan Utbah had been secreted out of the capital weeks before, along with the vast majority of the Majlis al-Shura, escaping to the northern stronghold of Tulaytullah. From there, they issued an act for the mobilisation of the general population, with tens of thousands of commoners conscripted into the army over the next few weeks.

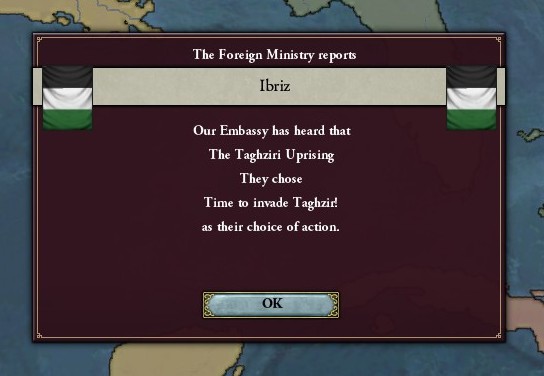

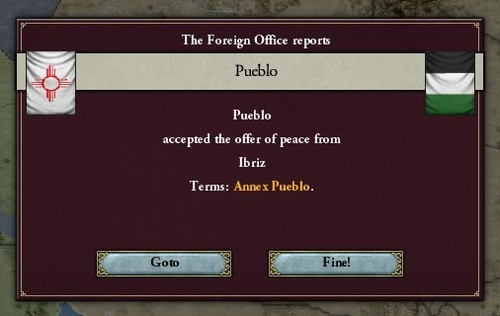

Whilst guns and uniforms were thrust into the arms of untrained labourers and peasants, rising tensions had exploded into war elsewhere, with the sabre-rattling revolutionaries in Ibriz instigating war in the Caribbean.

A crisis in the new world had quickly escalated in recent months, centred around the island of Taghzir, where demonstrations and protests had been growing in size and violence. Already fighting expensive wars against Al Andalus and Egypt, the Almoravid government didn’t have the resources to properly tackle yet another crisis, and thus dispatched a small army to brutally crush this uprising in its infancy.

And that they did, firing on and killing hundreds of protesters in a brutal, coordinated suppression campaign. This savagery drew the condemnations of surrounding powers, however, with politicans in Ibriz going beyond that even, and demanding that Morocco withdraw its forces from Taghzir altogether.

The Almoravid Sultan ignored this ultimatum, of course, but Ibriz would not be spurned. The Revolutionary Republic declared war on Morocco three days later, vowing to break the chains shackling Taghzir to the old world.

Back in Iberia, meanwhile, the mobilised armies were being put to good use. Some 50,000 levies were deployed to the western provinces, where they began retaking cities and fortresses from Moroccan garrisons, crushing the many revolts and uprisings as they did so.

Another 30,000 were sent south, travelling to Qurtubah by railway, and from there marching on Moroccan positions in Malaqah. Heavy fighting quickly followed, and through numbers alone, they managed to overrun the Berbers and force their retreat. Victory was theirs, however costly.

The Berbers withdrew to the strongly-fortified city of Qartayannat, where they could repulse any attempts to dislodge them.

The Andalusi had no interest in pursuing them, however, instead rushing to retake their capital further south. The next forty days would be arduous and relentless, largely consisting of street battles and citadel sieges, but the Andalusi would eventually crush the last Berber holdouts late in August - and Qadis, which never should’ve fallen, was finally retaken.

On the northern front, meanwhile, the Andalusi had met with much more success. After driving the bulk of the French armies northward, Astifadat al-Qutili launched a series of consolidation campaigns, securing control over vast tracts of Occitania and southern France.

And finally, the march on Paris began very late in December, with the historic city only coming into view in the dying hours of 1871, shrouded by the last sunset of the year.

By then, however, the French were a spent force. The Irish were rampaging across Britain, the Rhineland had been lost, half of France was under foreign occupation, and their capital of Paris was now under siege. There was no longer any doubts, they had lost the war.

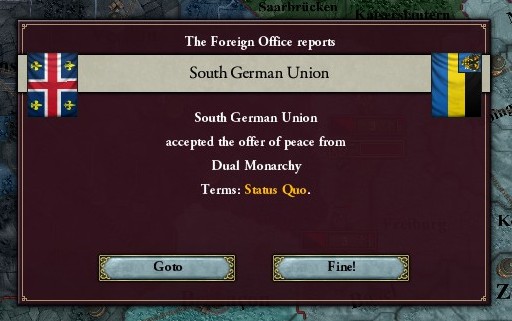

The ensuing peace conference was a surprisingly civil affair, after all the carnage and butchery of the past two years, with the Archduke of Bavaria making only one demand: that the Dual Monarchy withdraw its forces and diplomats from the Rhine Confederacy, surrendering its influence in the principality to the South German Union.

The French, who were in no position to negotiate, could only agree.

And with that, peace was finally re-established on the continent, though the war in Britain would continue to rage for years afterward. Exhausted and shattered French troops were quickly shipped across the Channel, but large parts of the army would mutiny in March of 1871, protesting their delayed payments, the authoritarian command of their generals, and the near-suicidal campaigns they’d been forced to endure.

To the east, meanwhile, another war came to a close. In sharp contrast to the battles of the Rhine Crisis, the Russians had easily vanquished their enemy in a series of decisive engagements stretching across the Baltic, pushing the Scandinavians back into their frozen peninsula.

Further south, the Egyptians had begun peace negotiations with Morocco, demanding that their rule in Cyrenaica be restored. The sheikhs of Cyrenaica had indeed been vassals to the Apanoub dynasty for centuries, only to be ripped away from them at the height of the Tirruni Wars, on the back of the successful Berber invasions of Egypt.

The coastal emirate had little strategic value now, however. The Almoravid Sultan agreed to renounce their earlier treaty and acknowledge Egytian rule in Cyrenaica, but only on his terms…

In return for Cyrenaica, Egypt would cut off their ties to Qadis, with a new alliance to be established between them and Morocco instead. King Apanoub had been cozying up to Al Andalus these past few years, but the Sack of Qadis had greatly diminished their standing on the world stage, so it didn’t take him very long to make his decision.

This was not good news for Al Andalus, who had hoped to win Egypt as an ally in future wars against Morocco.

At the moment, however, the Majlis had bigger worries to contend with. The conscripted armies were demobilised and dissolved, with the war-weary soldiers sent back to their hovels and farms, perhaps with fewer fingers and more bruises, but alive all the same.

The general mobilisation had hit the economy especially hard, however, with Al Andalus now steeped in war debts. The government immediately restructured the national budget, cutting expenses across the board and levying another harsh tax, determined to repay these debts and begin reconstruction efforts as soon as possible.

Apart from that, however, things were already looking up. Despite the obvious blemish in the Siege of Qadis, the past few years had not been completely disastrous, with a number naval bases constructed in the port-cities dotting the Iberian coasts, in the Atlantic islands and in the distant colonies in the Kongo.

The Imperialists had also begun efforts to claim the rich, fertile lands surrounding the Congo River, dispatching expeditions to negotiate trade agreements, broker vassalage agreements and eventually establish protectorates in South Angola.

And whilst war was raging in Europe, Balanabus Min-al-Bita had been launching imperialistic ventures deep into the largely-unexplored African interior, instigating war with the native kingdoms of Yaka and Kongo.

Eventually, after three years of campaigning, he managed to obtain valuable concessions from the native powers, gradually pushing the boundaries of Andalusi Africa outward in every direction.

Pushing across the tempestuous waves of the Atlantic, meanwhile, the war between Ibriz and Morocco continued to rage unabated. Despite being the aggressors in the conflict, the odds were certainly not in favour of Ibriz, with the revolutionaries facing the daunting alliance of Almoravid Morocco and the Dual Monarchy, along with their vassal states, junior partners and spherelings.

The Ibrizi strategy was simple: to strike hard and fast, and seize the initiative before the old world could retaliate. They set their sights on the Dual Monarchy first, and to prevent them from counter-attacking through Pueblo, the Revolutionary Armies forcibly occupied the native kingdom in an illegal, undeclared invasion.

From there, they pushed northward on a wide-ranging offensive, seizing control of a dozen forts, cities and towns as they swept across French Gharbia.

Back in Europe, the Mutinies of 1873 had hampered any attempts to repel the Celtic invasion of England. By the time the mutineers were captured and executed, Irish armies had reached London, forcing the parliament in Paris to make humiliating concessions to the Celtic Union.

And with that, for the first time in over a century, French rule in England was facing serious challenge.

In Iberia, meanwhile, the robust Andalusi economy quickly recovered in the post-war months. A hefty cash reserve was quickly stockpiled, with the vast majority of war debts repaid by Eid of 1874, making the Sultanate solvent once more.

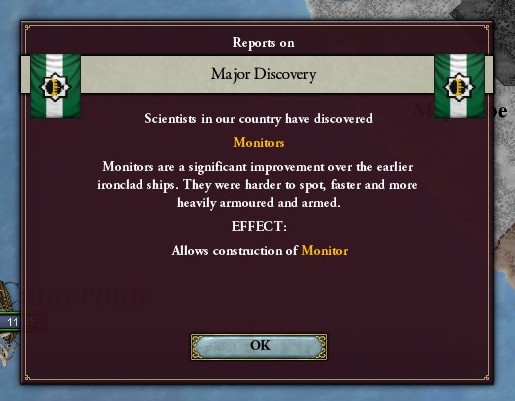

Whilst the moderates concerned themselves with tallying the accounts and completing payments, however, the Imperialists were investing in exciting naval advancements.

Building on intelligence gathered during the recent war, Andalusi shipwrights, architects and engineers began experimenting with new designs for ocean-going, steam-powered ships clad in armour and decked with artillery. These ironclads would be very expensive, but if they could be constructed en masse, then the Andalusi could well challenge the status quo on the high seas for the first time in…centuries.

That would have to wait for the future, however, because the year was quickly coming to a close - and with it, the Imperialists’ term in power.

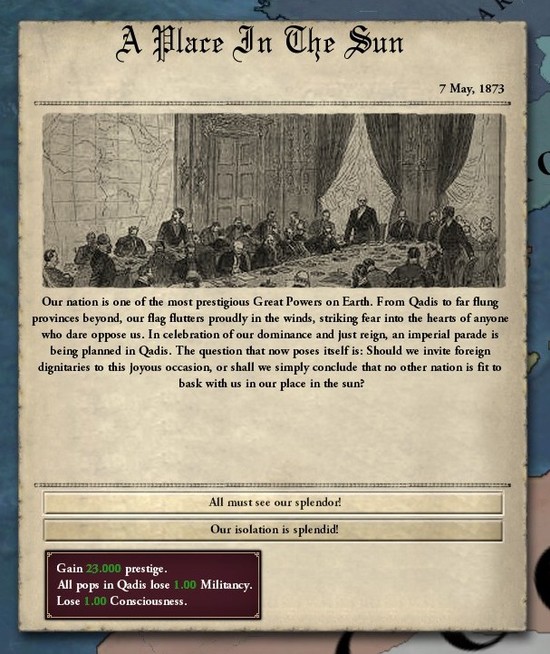

Despite the ups and downs of the past decade, Al Andalus emerges from the Rhine Crisis as a proven power on the world stage. The Moroccan invasions had been repulsed, Occitania and southern France had been occupied, and Andalusi armies had even reached the outskirts of Paris - these victories would not be forgotten.

Sultan Utbah thus organised and hosted an extravagant victory parade in Qadis, intent on reviving national pride and patriotism. Despite being an elderly man, the Sultan personally led the parade atop his chestnut mount (closely trailed by SGA agents), followed by field marshals and high-ranking viziers, who were in turn followed by 10,000 Andalusi veterans. The procession spent the better part of a day marching down the length of Qadis, surrounded by thronging crowds and swarming masses, all desperate to taste the splendour and opulence on display.

World map: